Illinois prison guard gets 20 years for inmate beating death

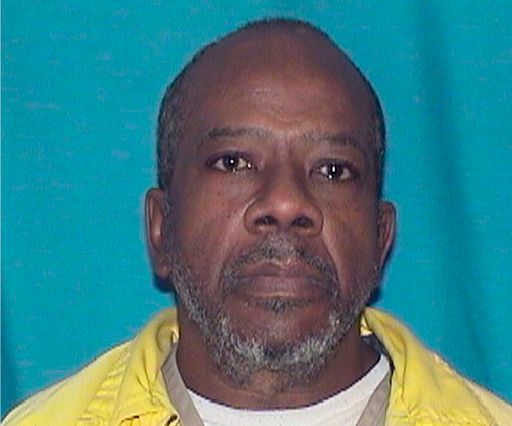

Earvin, who suffered from mental illness, was serving a six-year term for theft of merchandise under $300 in Cook County and was scheduled for release in September 2018. He also had a rap sheet dating to 1984.

By JOHN O'CONNOR | AP Political Writer

SPRINGFIELD, Ill. (AP) — A former Illinois state corrections officer was sentenced on Thursday to 20 years in federal prison for his role in the beating death of a prison inmate in May 2018.

Alex Banta, 31, of Quincy was “caught up in the culture” of silence surrounding violence against inmates but there was no excuse for his treatment of 65-year-old Larry Earvin at Western Illinois Correctional Center, U.S. District Judge Sue Myerscough said.

In a statement to the court, Banta expressed regret and took responsibility for his actions, but corroborated trial testimony that rough treatment of prisoners was not only condoned but expected at the prison in Mount Sterling, 250 miles (400 kilometers) southwest of Chicago.

Following a four-week trial, a jury convicted Banta in April 2022 of conspiracy to deprive civil rights, deprivation of civil rights, obstruction of an investigation, falsification of documents and misleading conduct.

Trial testimony revealed that Banta and co-defendants Todd Sheffler and Willie Hedden escorted Earvin, handcuffed behind his back, to the segregation unit vestibule where there were no security cameras, threw him so that his head banged into a wall, then kicked, punched and stomped him. Assistant U.S. Attorney Timothy Bass declared that the fatal blow to Earvin came when Banta jumped up and landed on the inmate’s abdomen with both knees.

He faced up to life in prison. Myerscough sentenced him to 15 years on the civil rights charges and five years on the other counts, to run consecutively.

“You were one of the younger officers caught up in the culture at Western of ‘see no evil’ and ‘snitches get stitches,’ which you learned from your superiors, but it in no way excuses your conduct," Myerscough said. “The governor has replaced the warden and implemented other reforms, so hopefully this culture has changed already.”

Earvin's beating on May 17, 2018, resulted in 15 broken ribs and abdominal injuries so severe that a portion of his bowel was surgically removed. He died June 26.

“What type of person does it take to assault a 65-year-old man who's handcuffed behind his back?" remarked Earvin's brother Willie Earvin Jr., 74, who testified for the prosecution. "I'm a Vietnam veteran and we weren't allowed to do that to prisoners."

In his statement to the court before sentencing, Banta, who looked downward during the bulk of the proceedings, noted his apology would mean little to a federal judge who likely heard it repeatedly from defendants before her, but said he regretted his actions and the pain he caused Earvin's family.

He said he went to work at Western in 2014 to support his family “but I had no idea how the job was going to change me." He described an atmosphere where he was instructed from the get-go to look away from indiscretions.

“On my first day, during orientation, Internal Affairs (officers) asked the supervisory staff to leave and then started to tell us, ‘Forget what you learned at the academy. We do things differently here,’” Banta said. “'Things will happen that you might need to ignore. If things happen with an inmate, aim for the body and not the face.'"

A request for comment was emailed to the Illinois Department of Corrections spokesperson.

Earvin, who suffered from mental illness, was serving a six-year term for theft of merchandise under $300 in Cook County and was scheduled for release in September 2018. He also had a rap sheet dating to 1984.

But his son, Larry Pippion, 51, questioned why he was locked up for a petty crime when he was mentally ill.

“Isn't there another way to get him help instead of just throwing him away?” Pippion asked. Myerscough later called that fact “an indictment of our system.”

Other guards at Western that day testified that Earvin, having reported too late for a break in the yard, refused to return to his cell and allegedly became combative. That prompted an “officer in distress” call to which all available officers are required to respond. Dozens did so and then several, including Banta, escorted him to the segregation unit.

Sheffler was tried with Banta but the jury that convicted Banta was hung on Sheffler. He was retried last summer and convicted of the same counts as Banta in August. Hedden pleaded guilty in March 2021 to the more serious charges and testified against both Banta and Sheffler.

Hedden testified Thursday that he witnessed Banta punch and kick another inmate a few years before the incident with Earvin. On cross-examination, he wouldn't go so far as to say violence against inmates was unstated policy, but he said superiors were aware of it and “it was too prevalent. It happened all too often.”

The Chicago Journal needs your support.

At just $20/year, your subscription not only helps us grow, it helps maintain our commitment to independent publishing.

If you're already a subscriber and you'd like to send a tip to continue to support the Chicago Journal, which we would greatly appreciate, you can do so at the following link:

Send a tip to the Chicago Journal